In labs chilled to 4 kelvins (-450 degrees!) and on expeditions to polar regions, Georgia Tech scientists are discovering how extreme cold simultaneously challenges and advances technology in computing, space exploration, and the interpretation of Earth’s natural signals.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

While Italy’s 2026 Winter Olympics draw the world’s attention to snow and ice, Georgia Tech researchers are also confronting cold at its most extreme.

Some labs in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) use liquid nitrogen and liquid helium to chill cryogenic test systems to as low as 4 Kelvins (K), or -452.47 degrees Fahrenheit (F), temperatures that rival the coldest regions of deep space.

At this point, materials and electronic devices stop behaving in familiar ways, which is exactly why some ECE researchers use these extreme conditions to explore and develop technologies for extraterrestrial environments and advanced and quantum computing applications.

Other ECE teams work in natural extremes, carrying instruments into polar regions where the cold creates opportunities that no lab can fully replicate.

Just as cold pushes athletes in different ways, it guides ECE research down its own distinct paths.

Semiconductor Struggles in Subzero

For Professor John Cressler, the cold can be both an adversary and an ally.

Some semiconductor device technologies can essentially be shut down by extreme cold.

“Electronics are very temperature dependent,” Cressler said, whose lab houses cryogenic test systems. “Whether you see it or not, every electronic you buy has a tested temperature spec associated with it.”

Current commercially sold devices, including most cell phones, aren't made to run in environments colder than 32 F.

“Semiconductors only work when electrons are able to flow through them,” Cressler said. “When the temperature drops, the number of electrons that are able to flow through it, also known as carrier density, goes way down. If all the electrons are gone, then you can’t move a current.”

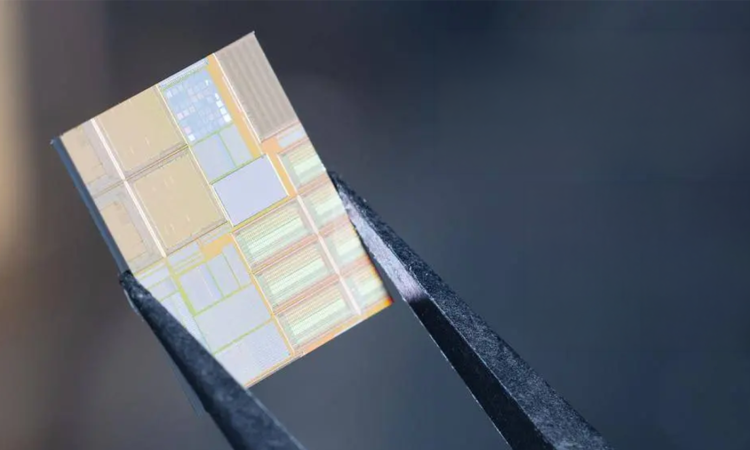

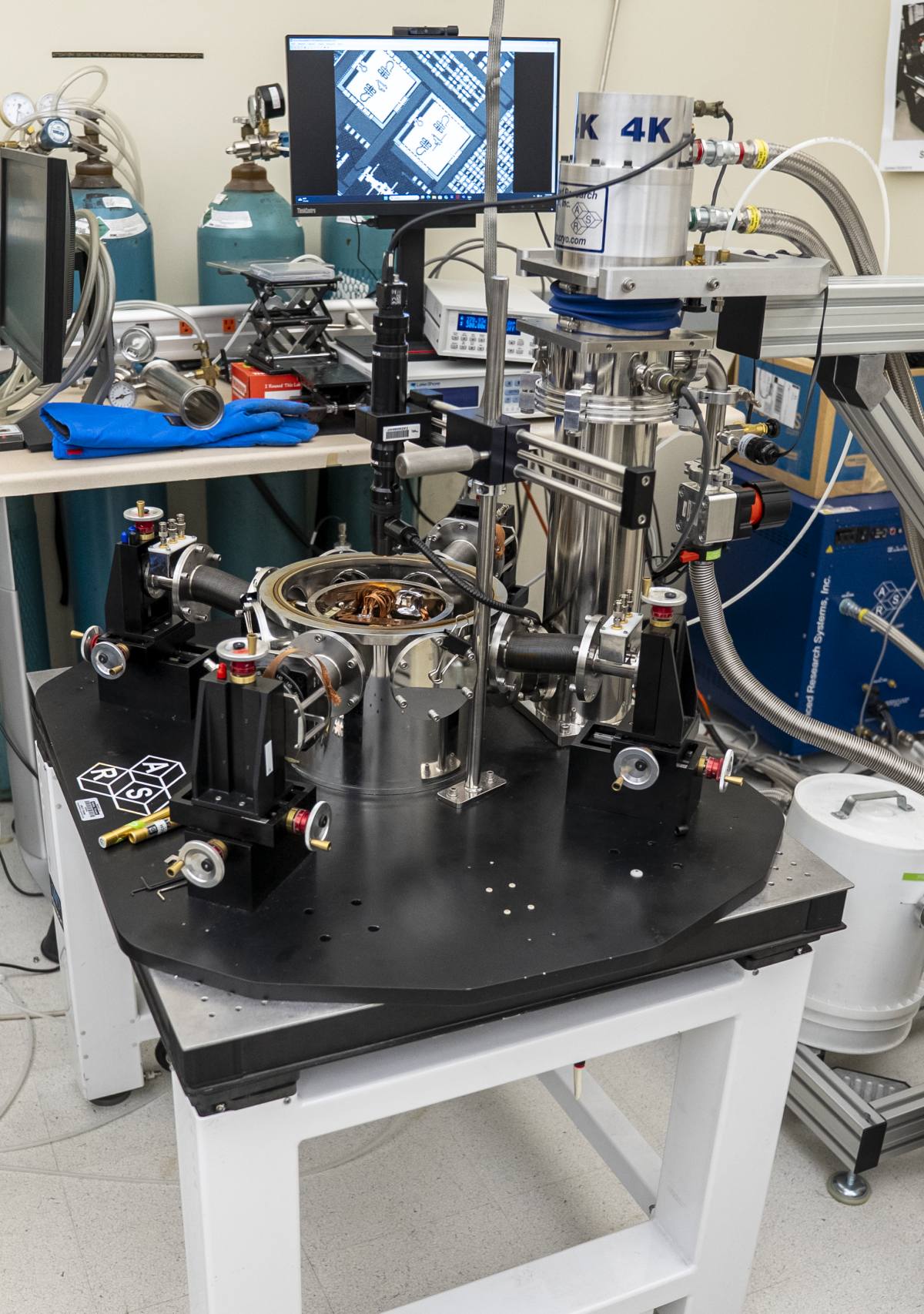

Cressler and the students in his lab use cryogenic testing systems to observe the behavior of different materials at extreme cold temperatures and high levels of radiation.

His research focuses on materials such as silicon-germanium, which can maintain the necessary carrier density at cold temperatures, and even run faster the colder it gets. His lab has become a global leader in this field.

“Using silicon-germanium, we were able to create devices that worked in space-like conditions, which can be as cold as 25K and in the presence of high radiation,” Cressler said. “Many other generic semiconductor materials essentially become insulators or break down in those conditions.”

Previous missions to the Moon and Mars, where temperatures can get as low as 50K (-369.67 F) have put instruments in protective “warm boxes” to maintain Earth-like conditions, which can be limiting to science capabilities.

“It’s essentially a heavily shielded oven, which is heavy and expensive to launch,” Cressler said. “It costs about a million dollars per pound to get something into orbit. It also prevents instruments from being able to autonomously operate out in the space environment.”

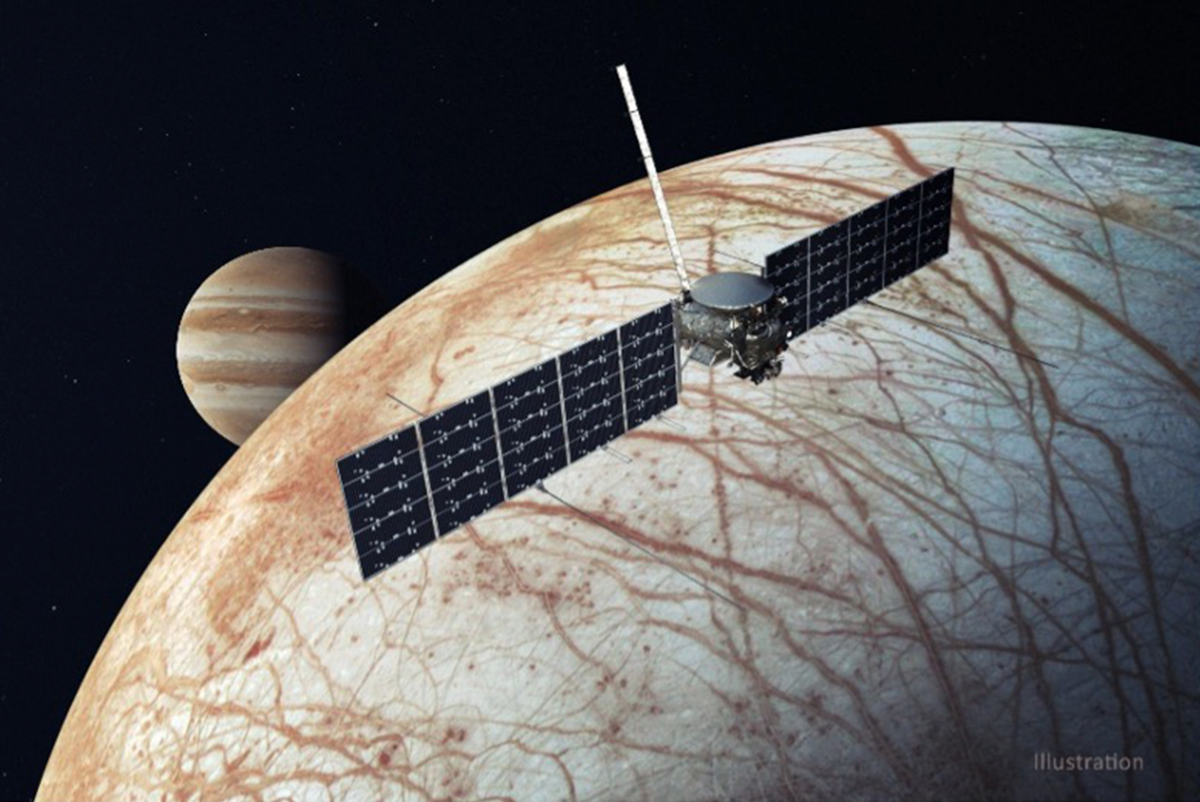

Silicon-germanium has shown great promise and has even been recognized by NASA’s Concepts for Ocean Worlds Life Detection Technology program as having potential uses on missions to Jupiter’s moon, Europa — where surface temperatures never exceed –225 F and liquid water oceans may lie beneath the ice.

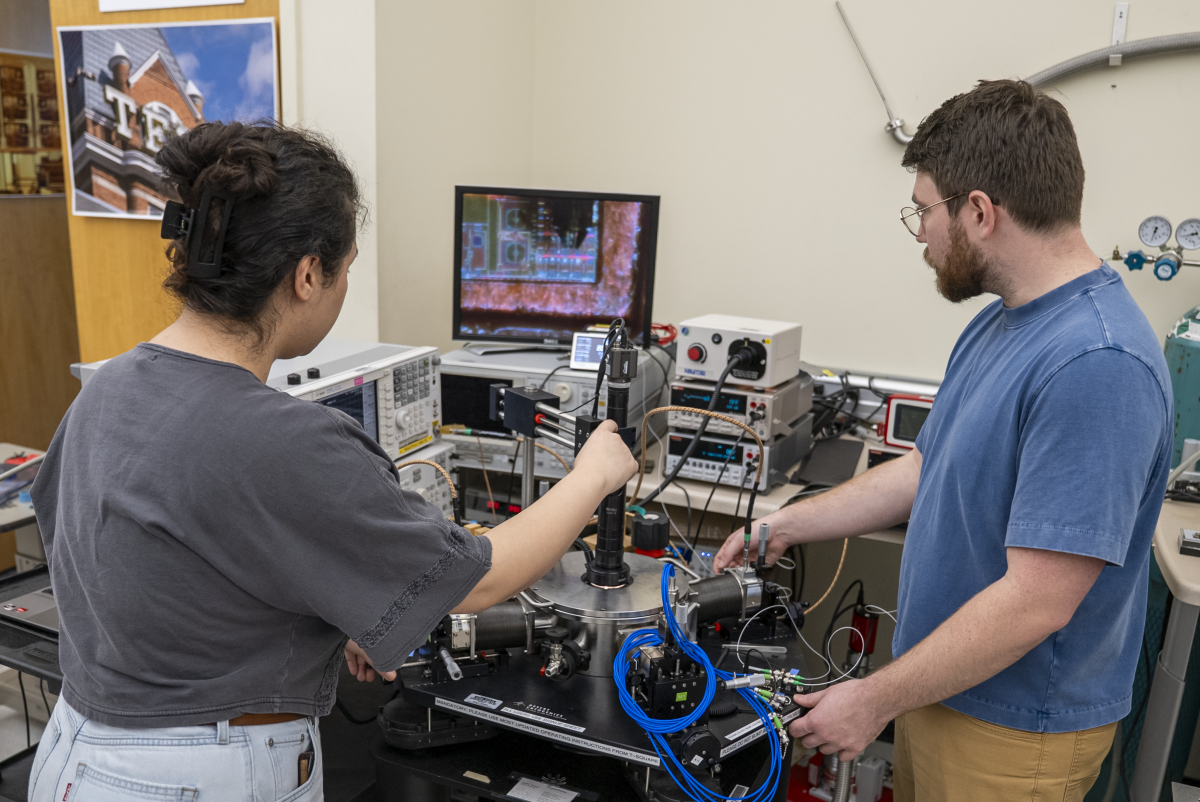

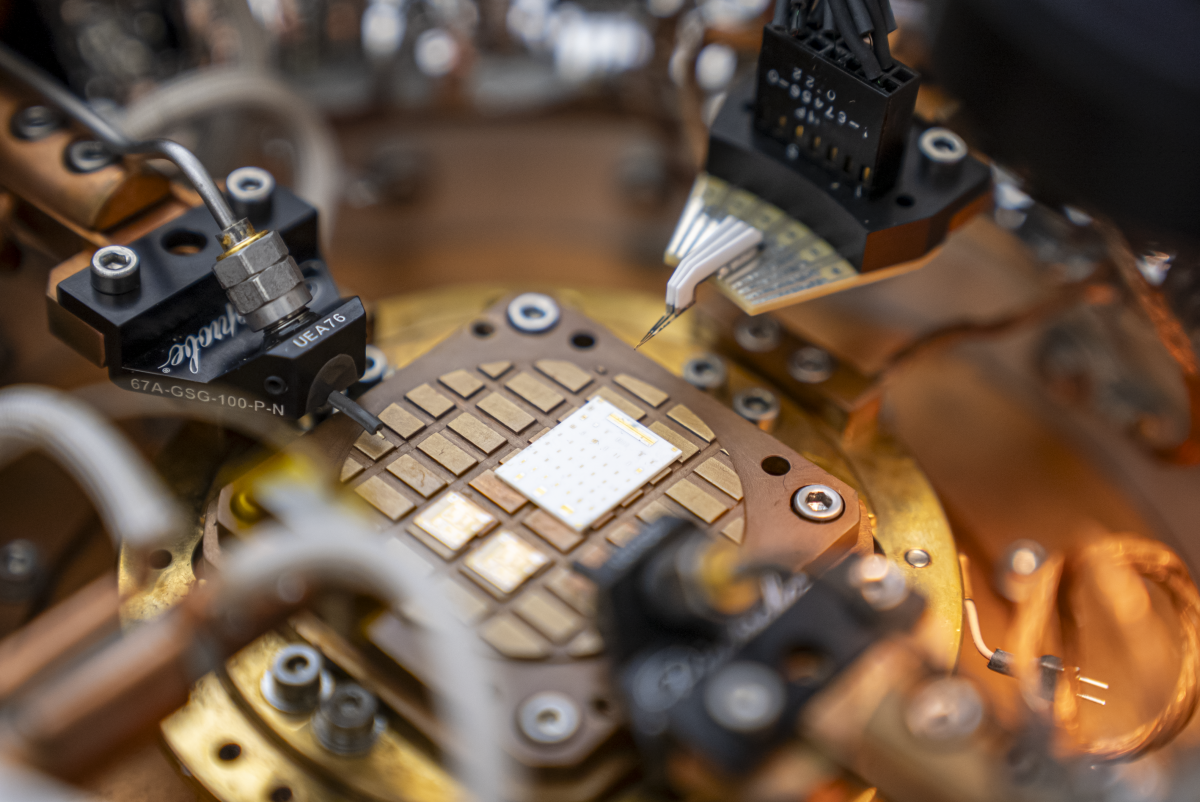

Fourth-year Ph.D. student Zachary Brumbach and fifth-year Ph.D. student Mozhgan Hosseinzadeh in Professor Cressler's lab using the vacuum-sealed cryogenic testing system to observe a chip in temperatures as low as 4K.

An artist rendering of one of Jupiter's moons, Europa, where Cressler's technology may someday be deployed to get readings from the surface.

Memory Thrives in Cold

While the cold might be an obstacle to Cressler, it’s an opportunity for Professor Shimeng Yu’s research.

He has been studying cryogenic computer memory technology, which improves in colder temperatures.

A study funded by the National Science Foundation, which he completed with Associate Professor Asif Khan, tested emerging ferroelectric and resistive memory technology between 4K (-452.47 F) and 77K (-321.07 F).

It found that memory can be more reliable, hold more data, and hold the data for longer at lower temperatures.

“It reduces the thermal activations in devices, which is usually what leads to the degradation of memory devices,” Yu said. “It also helps reduce the fluctuation of thermal noise within the device, which improves memory capability. At these temperatures, a chip that previously held 100 gigabytes of data might now be able to hold 200 gigabytes.”

While promising, it isn’t without its drawbacks.

“There’s no free lunch,” Yu said. “The downside is a need for more voltage.”

The study also found that the loss of thermodynamics due to the colder temperatures creates the need for more power elsewhere to run the memory device.

“Before, when we needed two volts, we might need three now,” Yu said. “So, we have to inject more electrical stimulus to compensate for the loss of thermal energy."

Other ECE faculty are exploring the logic side of the stack at the same frigid temperatures. Like memory technology, complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS)—the transistor technology that underpins nearly all modern chips—also changes character in the deep‑cold. Professors Arijit Raychowdhury and Suman Datta are advancing cryogenic CMOS circuits that can switch reliably, maintain signal integrity, and interface with sensors and memories at temperatures far below conventional operating limits.

Cooling for Quantum

The exploration of memory and logic in extreme temperatures also feeds into one of today’s most ambitious technologies: quantum computing, which operates at about 10 to 100 millikelvins (about -460 F). This is required to maintain the coherence of the fundamental unit of information in quantum computing, called qubits.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

“We may not be working on the core of quantum computing because that requires even lower temperatures that few places can achieve, but all our work in ECE, though operating in the periphery, is assisting in the overall qubit operation.”

Professor Shimeng Yu

Unlike classical bits, which represent either a zero or one, qubits can exist in multiple states at once through a property called superposition, and they can become linked through entanglement. These quantum effects allow certain computations to be performed far more efficiently than on traditional machines.

“We may not be working on the core of quantum computing because that requires even lower temperatures that few places can achieve, but all our work in ECE, though operating in the periphery, is assisting in the overall qubit operation,” said Yu.

That “periphery” is essential.

Even the most advanced quantum processor still relies on classical electronics for control signals, timing, amplification, and memory—all of which must function inches away from qubits kept near absolute zero.

According to Yu, developing reliable devices and materials under those extreme conditions is what will enable quantum systems to scale beyond the lab.

From the Lab to the Frozen Tundra

The cold isn’t confined to the lab. For some ECE teams, it’s a destination.

ECE students and researchers in Professor Morris Cohen’s Low Frequency Radio Group frequently go to remote frozen locations such as Alaska and Antarctica for atmospheric research.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Sensors inside the cryogenic testing system.

“The cold itself is not the advantage; it is the environment that comes with it," Cohen said. "In the polar regions, the cold contributes to isolation, very little lightning, and almost no radio noise. That quiet is what lets us better "listen" to the lightning‑generated signals we study.”

Several students have gone to the Polar Aeronomy and Radio Science (PARS) summer school program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program to map the upper atmosphere and better understand the highly charged layer of the atmosphere, known as the ionosphere. This work contributes to important functions like better GPS.

In 2024, Ph.D. student Shweta Dutta took the long trip to Horseshoe Island, Antarctica, to evaluate whether the site could host a very low frequency (VLF) antenna to detect “whistlers,” lightning‑driven signals that reveal how energy travels through the ionosphere.

After collecting some data successfully, the following year, an antenna was semi-permanently installed. It was powered by solar panels and battery banks, so it continues to record for many months even when the station is unmanned during the Antarctic winter.

Ph.D. student Shweta Dutta traveled to Antarctica to investigate the mysteries of the Earth’s electromagnetic field.

Ph.D. student Jeremiah Lightner on his third research trip to Alaska.

Back in Atlanta, the field recordings join decades of low‑frequency data collected across the world. Through the open WALDO archive — the Worldwide Archive of Low‑frequency Data and Observations — Cohen’s group and collaborators are digitizing and sharing these global measurements.

The goal is to give scientists a clearer picture of how energy moves between the atmosphere and near‑Earth space, and to support models that help keep satellites and essential systems resilient.

Whether created in the lab or found at the edges of the world, the cold old brings into view what ordinary temperatures often hide. These conditions continue to reveal both challenges and opportunities, drawing ECE researchers deeper into these extreme conditions in search of answers.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Content

Engineering the Car of the Future

ECE experts look to the future of the automotive industry, and how new technology—from innovations in electric motors, wireless charging, autonomous systems, and beyond—will not only transform vehicles, but reshape the power grid, influence policy decisions, and impact numerous aspects of society.

Smaller, Smarter, Speedier, Stacked: Engineering Next-Gen Computing

Some technologists suggest we’re nearing the limits of packing ever-more computing power into ever-smaller chips. At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.