A research collaboration consisting of IHP-Innovations for High Performance Microelectronics in Germany and the Georgia Institute of Technology has demonstrated the world's fastest silicon-based device to date. The investigators operated a silicon-germanium (SiGe) transistor at 798 gigahertz (GHz) fMAX, exceeding the previous speed record for silicon-germanium chips by about 200 GHz.

A research collaboration consisting of IHP-Innovations for High Performance Microelectronics in Germany and the Georgia Institute of Technology has demonstrated the world's fastest silicon-based device to date. The investigators operated a silicon-germanium (SiGe) transistor at 798 gigahertz (GHz) fMAX, exceeding the previous speed record for silicon-germanium chips by about 200 GHz.

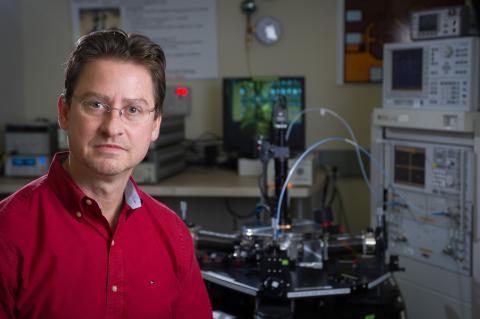

Although these operating speeds were achieved at extremely cold temperatures, the research suggests that record speeds at room temperature aren't far off, said professor John D. Cressler, who led the research for Georgia Tech. Information about the research was published in February 2014, by IEEE Electron Device Letters.

"The transistor we tested was a conservative design, and the results indicate that there is significant potential to achieve similar speeds at room temperature – which would enable potentially world changing progress in high data rate wireless and wired communications, as well as signal processing, imaging, sensing and radar applications," said Cressler, who hold the Schlumberger Chair in electronics in the Georgia Tech School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. "Moreover, I believe that these results also indicate that the goal of breaking the so called ‘terahertz barrier’ – meaning, achieving terahertz speeds in a robust and manufacturable silicon-germanium transistor – is within reach."

Meanwhile, Cressler added, the tested transistor itself could be practical as is for certain cold-temperature applications. In particular, it could be used in its present form for demanding electronics applications in outer space, where temperatures can be extremely low.

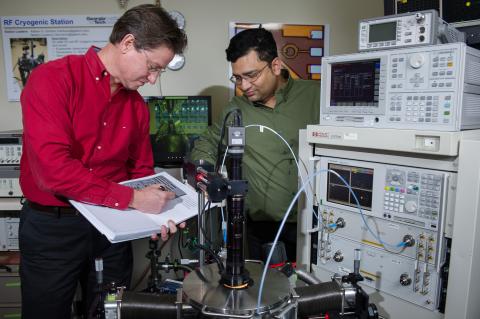

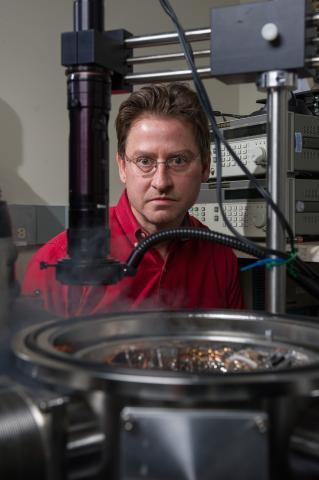

IHP, a research center funded by the German government, designed and fabricated the device, a heterojunction bipolar transistor (HBT) made from a nanoscale SiGe alloy embedded within a silicon transistor. Cressler and his Georgia Tech team, including graduate students Partha S. Chakraborty, Adilson S. Cardoso and Brian R. Wier, performed the exacting work of analyzing, testing and evaluating the novel transistor.

“The record low temperature results show the potential for further increasing the transistor speed toward terahertz (THz) at room temperature. This could help enable applications of Si-based technologies in areas in which compound semiconductor technologies are dominant today. At IHP, B. Heinemann, H. Rücker, and A. Fox supported by the whole technology team working to develop the next THz transistor generation,” according to Bernd Tillack, who is leading the technology department at IHP in Frankfurt (Oder), Germany.

Silicon, a material used in the manufacture of most modern microchips, is not competitive with other materials when it comes to the extremely high performance levels needed for certain types of emerging wireless and wired communications, signal processing, radar and other applications. Certain highly specialized and costly materials – such as indium phosphide, gallium arsenide and gallium nitride – presently dominate these highly demanding application areas.

But silicon-germanium changes this situation. In SiGe technology, small amounts of germanium are introduced into silicon wafers at the atomic scale during the standard manufacturing process, boosting performance substantially.

The result is cutting-edge silicon germanium devices such as the IHP Microelectronics 800 GHz transistor. Such designs combine SiGe's extremely high performance with silicon's traditional advantages – low cost, high yield, smaller size and high levels of integration and manufacturability – making silicon with added germanium highly competitive with the other materials.

Cressler and his team demonstrated the 800 GHz transistor speed at 4.3 Kelvins (452 degrees below zero, Fahrenheit). This transistor has a breakdown voltage of 1.7 V, a value which is adequate for most intended applications.

The 800 GHz transistor was manufactured using IHP’s 130-nanometer BiCMOS process, which has a cost advantage compared with today’s highly-scaled CMOS technologies. This 130 nm SiGe BiCMOS process is offered by IHP in a multi-project wafer foundry service.

The Georgia Tech team used liquid helium to achieve the extremely low cryogenic temperatures of 4.3 Kelvins in achieving the observed 798 GHz speeds. "When we tested the IHP 800 GHz transistor at room temperature during our evaluation, it operated at 417 GHz," Cressler said. "At that speed, it's already faster than 98 percent of all the transistors available right now."

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contacts:

Georgia Tech: John Toon (404894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu) or Brett Israel (404-385-1933) (brett.israel@comm.gatech.edu).

IHP: Dr. Wolfgang Kissinger (kissinger@ihp-microelectronics.com)

Writer: Rick Robinson

Additional Images