Direct current (DC) powers flashlights, smartphones and electric cars, but major power users depend on alternating current (AC), which cycles on and off 60 times per second. Among the reasons: AC is simple to turn off when there’s a problem — known as a fault — such as a tree falling on a power line.

Direct current (DC) powers flashlights, smartphones and electric cars, but major power users depend on alternating current (AC), which cycles on and off 60 times per second. Among the reasons: AC is simple to turn off when there’s a problem — known as a fault — such as a tree falling on a power line.

But DC has inherent advantages over its alternating cousin, among them higher efficiency and the ability to carry more power over longer distances. That could be increasingly important as wind farms in rural areas produce power needed in population centers. And future electric aircraft and ships are likely to be powered by high-power-density DC systems.

Alternating current can be shut down when the power level hits zero during a cycle — the zero-crossing point of a sine wave — which is the basis for breakers that protect modern power systems everywhere from substations to home installations. Without these alternating cycles, however, direct current has no opportune time to turn off the power.

New technology funded by a $3.3 million award from ARPA-E’s BREAKERS program could help solve that problem using innovations in power electronics, piezoelectric actuators, and new insulation materials to make high-power DC circuit breakers feasible. Researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Florida State University (FSU) expect to enable breaker switching speeds ten times faster than existing equipment and commercialize the technology through a consortium of industry partners.

“The transition from AC to DC, which is already happening, will open up a new paradigm for efficiently and controllably managing power in future electrical systems and military platforms,” said Michael "Mischa" Steurer, a research faculty member at Florida State University’s Center for Advanced Power Systems. “This will be enabled by the amazing developments that have happened over the past two decades in power electronics.”

The hybrid circuit breaker under development by the research team will use stacks of very large transistors to switch off the DC when necessary. Semiconductors are less efficient at conducting current than conventional mechanical switches, so under ordinary conditions, the current will flow through mechanical switches. But when the power must be turned off, current will be briefly routed through the power electronics until the mechanical breakers can be opened.

“We are proposing a hybrid DC circuit breaker in which the current will have two paths,” explained Lukas Graber, an assistant professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Georgia Tech. “One path will be through the semiconductors, which can interrupt the current when needed. The second path will be through mechanical switches, which will provide a much less resistive path that will be more efficient for normal operations.”

In common consumer electronics applications, transistors are too small to see and handle just a few volts. The transistors that will be used in DC switching are much larger — a square centimeter — and dozens or hundreds of them would be combined in serial or parallel to provide enough capacity for switching thousands of volts. After the current has been moved to the solid-state transistor pathway, piezoelectric actuators will quickly separate the contacts in the mechanical switches before current rises too high in the transistors. Once separated, the current through the transistors can be switched off.

“We need to be extremely fast,” Graber said. “We have to separate the contacts within 250 microseconds and to completely break the current within 500 microseconds — just half a millisecond. For that reason, we cannot use spring-loaded or hydraulic actuators common to AC breakers. Devices that rely on the piezoelectric effect can do that for us.”

The Georgia Tech and FSU researchers have developed intellectual property for components of the proposed DC breakers, and will work together to combine the technologies. The project is known as Efficient DC Interrupter with Surge Protection (EDISON).

“We will combine the strengths of significantly different technologies — solid state and mechanical — into a system that functions better overall than its individual components,” said Steurer. “The pieces of the system have to work together seamlessly within half a millisecond to achieve our goal.”

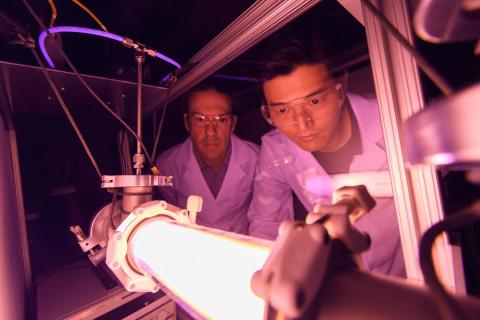

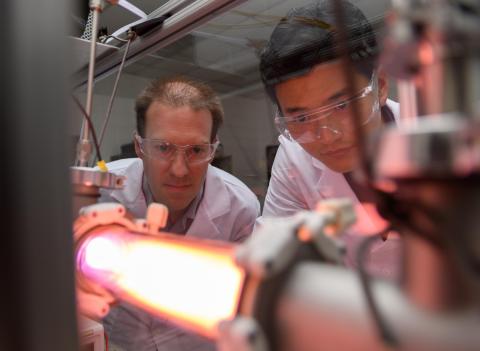

The researchers — including Associate Professor Maryam Saeedifard, VentureLab Principal Jonathan Goldman, and Postdoctoral Fellow Chanyeop Park at Georgia Tech and Professor Fang Peng, Research Faculty Karl Schoder, and Assistant Professor Yuan Li at FSU — expect to build a prototype that will be tested at FSU’s five-megawatt test facility within three years. The development and testing will be done in collaboration with a team of industrial partners who will ultimately transition the DC breakers to commercial use.

Direct current could be particularly useful as more renewable energy comes online. Photovoltaics in the west may still be generating power after the sun sets in the east. Wind turbines may be producing power in the midsection of the country while clouds cover other parts of the country. Transmitting power from one location to another could therefore become more important.

“There are large distances to be bridged with renewables,” Graber said. “When we rethink what the next grid is going to be like, DC may play a larger role.”

For those who know the history of electrical power, the work opens a new chapter of a story that goes back almost a century and a half to two of the most celebrated inventors of all time.

The relative merits of DC versus AC provided the basis for the “War of Current” between inventors Thomas Edison and Nickolas Tesla in the 1880s. Edison, a proponent of DC, ultimately lost out to Tesla’s AC. But had Edison been able to use modern power electronics, the story might have turned out differently.

“Edison was right, but at the time he was wrong,” Graber said. “DC is coming back strong, and we will be a part of making it practical.”

Funding for the work is from ARPA-E’s Building Reliable Electronics to Achieve Kilovolt Effective Ratings Safely (BREAKERS) program. The project was among eight funded to support the development of medium-voltage devices for grid, industry and transportation applications.

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contact: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu)

Writer: John Toon

Additional Images