Ph.D. student Anthony Spears explores Antarctica's icy waters with help from an autonomous underwater vehicle called Icefin.

This past fall, Ph.D. student Anthony Spears’ studies with the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) at Georgia Tech took him to one of the most remote places on earth. Spears spent October and November in Antarctica as part of Georgia Tech’s Sub-Ice Marine and PLanetary-analog Ecosystems (SIMPLE) team. The SIMPLE team is made up of researchers from ECE, the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), and the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, as well as other research institutions across the United States. Their research involves the design, development, and testing of an autonomous underwater vehicle for use in polar regions.

The team’s focus is on the formation and evolution of icy ocean environments that mimic the conditions on Jupiter’s innermost moon, Europa. Their findings will help determine if Europa could support life and inform future exploration to the icy moon.

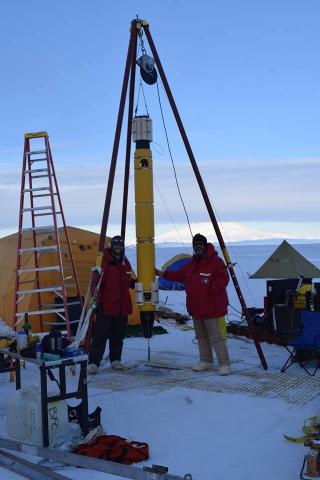

Funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the expedition centered on the deployment of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) including Georgia Tech’s Icefin vehicle, which was designed to collect video and other scientific data from under the Ross Ice Shelf near McMurdo Station, Antarctica. In addition to assisting with the development and design of Icefin, Spears, who is advised by ECE Professor Ayanna Howard, helped with the deployment and data collection. Spears’ Ph.D. research will use the data collected from this trip in the development of algorithms that will improve future under-ice navigation systems.

The vehicle itself combines portability with a large suite of instrumentation used for analyzing the under-ice conditions. It is a modular vehicle, which allows each part to be broken down and modified separately. Icefin is rated to go down to 1500 meters and can withstand temperatures of -40°C. It has five directional thrusters for motion, two cameras, sonars, a conductivity-temperature sensor, a depth sensor, and an altimeter. Also included are a Doppler velocity log and an inertial measurement unit for sensors. These aid in localization of the vehicle as compasses cannot be used at such an extreme latitude.

After deployment and testing in a ten meter diameter test tank, Icefin was ready for its maiden voyage under the ice. On November 23, 2014 Icefin was successfully deployed in a dive jetty (a large hole used by ice divers) near McMurdo Station. Four days later, it was taken out to the Ross Ice Shelf where a team of ice drillers had already drilled a hole through the 14-meter thick ice. Using a tether and winch system with a 15-foot tripod, the vehicle was lowered into the ice the following day. Descending to a 500 meter depth at the bottom of the ocean, Icefin recorded data from a location never seen by humans. In addition to scientific data measuring currents, temperature, and depth, the vehicle gathered images of sea life including sea stars, brittle stars, crustaceans, anemones, and sponges. The fact that such a severe habitat is able to sustain life was of great interest to the SIMPLE team and could point to possible life in similar environments such as Europa.

While Icefin’s missions were successful, the isolation and harsh environment posed challenges to the team during their two months in the field. “The challenge in doing engineering work with such a complex vehicle without the regular infrastructure available to us in Atlanta proved difficult,” said Spears. “We were limited in capabilities, materials, tools, and human support. For instance, if a new part needed to be ordered, it would take multiple weeks to arrive. We were forced to be creative to solve any problems that would arise.”

The extreme cold was another factor for the group. “The harsh environment is something you think about abstractly in the planning stages, but when you are out in sub-zero weather trying to thread a tiny screw through two layers of gloves without dropping it in the snow, or driving 20 miles on a snowmobile to the hole site, it takes on a whole new meaning,” said Spears.

Spears’ trip represents the first of many more for the Icefin vehicle and its team. Icefin performed its designed duties as an exploratory probe and was able to collect images and data from areas under the ice that had not been previously explored. Now that researchers know Icefin is working as designed, tweaks can be made for missions that are longer in duration in which more data can be acquired.

Icefin’s next mission is planned for 2016 in Greenland. In the meantime, the SIMPLE team will keep Icefin closer to home by testing and fine tuning it at GTRI-Savannah and even at the pool at the Georgia Tech Campus Recreation Center.

Spears is unsure if he’ll participate in the Greenland trip, but feels fortunate to have been a part of the project thus far. He said, “It was an amazing experience to do robotics work out in the field at the bottom of the world. I can't wait to uncover the Icefin vehicle’s potential as it readies for its future missions to the polar regions of our planet.”

Additional Images