A simulator that comes complete with a virtual explosion could help the operators of chemical processing plants – and other industrial facilities – learn to detect attacks by hackers bent on causing mayhem. The simulator will also help students and researchers understand better the security issues of industrial control systems.

A simulator that comes complete with a virtual explosion could help the operators of chemical processing plants – and other industrial facilities – learn to detect attacks by hackers bent on causing mayhem. The simulator will also help students and researchers understand better the security issues of industrial control systems.

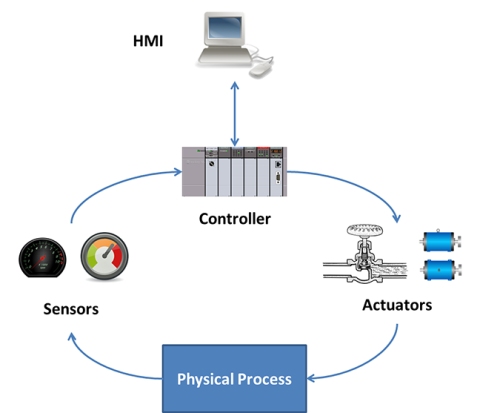

Facilities such as electric power networks, manufacturing operations and water purification plants are among the potential targets for malicious actors because they use programmable logic controllers (PLCs) to open and close valves, redirect electricity flows and manage large pieces of machinery. Efforts are underway to secure these facilities, and helping operators become more skilled at detecting potential attacks is a key part of improving security.

“The goal is to give operators, researchers and students experience with attacking systems, detecting attacks and also seeing the consequences of manipulating the physical processes in these systems,” said Raheem Beyah, the Motorola Foundation Professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “This system allows operators to learn what kinds of things will happen. Our goal is to make sure the good guys get this experience so they can respond appropriately.”

Details of the simulator were presented August 8 at Black Hat USA 2018, and August 13 at the 2018 USENIX Workshop on Advances in Security Education. The simulator was developed in part by Atlanta security startup company Fortiphyd Logic, and supported by the Georgia Research Alliance.

The simulated chemical processing plant, known as the Graphical Realism Framework for Industrial Control Simulations (GRFICS), allows users to play the roles of both attackers and defenders – with separate views provided. The attackers might take control of valves in the plant to build up pressure in a reaction vessel to cause an explosion. The defenders have to watch for signs of attack and make sure security systems remain operational.

Of great concern is the “man-in-the-middle” attack in which a bad actor breaks into the facility’s control system – and also takes control of the sensors and instruments that provide feedback to the operators. By gaining control of sensors and valve position indicators, the attacker could send false readings that would reassure the operators – while the damage proceeded.

“The pressure and reactant levels could be made to seem normal to the operators, while the pressure is building toward a dangerous point,” Beyah said. Though the readings may appear normal, however, a knowledgeable operator might still detect clues that the system has been attacked. “The more the operators know the process, the harder it will be to fool them,” he said.

The GRFICS system was built using an existing chemical processing plant simulator, as well as a 3D video gaming engine running on Linux virtual machines. At its heart is the software that runs PLCs, which can be changed out to represent different types of controllers appropriate to a range of facilities. The human-machine interface can also be altered as needed to show a realistic operator control panel monitoring reaction parameters and valve controller positions.

“This is a complete virtual network, so you can set up your own entry detection rules and play on the defensive side to see whether or not your defenses are detecting the attacks,” said David Formby, a Georgia Tech postdoctoral researcher who has launched Fortiphyd Logic with Beyah to develop industrial control security products. “We provide access to simulated physical systems that allow students and operators to repeatedly study different parameters and scenarios.”

GRFICS is currently available as an open source, free download for use by classes or individuals. It runs on a laptop, but because of heavy use of graphics, requires considerable processing power and memory. An online version is planned, and future versions will simulate the electric power grid, water and wastewater treatment facilities, manufacturing facilities and other users of PLCs.

Formby hopes GRFICS will expand the number of people who have experience with the security of industrial control systems.

“We want to open this space up to more people,” he said. “It’s very difficult now to find people who have the right experience. We haven’t seen many attacks on these systems yet, but that’s not because they are secure. The barrier for people who want to work in the cyber-physical security space is high right now, and we want to lower that.”

Beyah and Formby have been working for several years to increase awareness of the vulnerabilities inherent in industrial control systems. While the community still has more to do, Beyah is encouraged.

“Several years ago, we talked to a lot of process control engineers as part of the NSF’s I-Corps program,” he said. “It was clear that for many of these folks then, security was not a major concern. But we’ve seen changes, and lots of people are now taking system security seriously.”

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Assistance: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu)

Writer: John Toon

Additional Images