Omer Inan and his former colleague from Countryman Associates, Chris Countryman, received an Academy Award for Technical Achievement for their work on a series of sub-miniature lavalier microphones.

As career highlights go, most Georgia Tech School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) faculty look forward to becoming IEEE Fellows, CAREER Award winners, perhaps even a member of the coveted National Academy of Engineering (NAE). Few have set their sights on acclaim from another academy: the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (popularly known as the Oscars®), including ECE associate professor Omer Inan. But on January 6, 2021, Inan unexpectedly received an email from David Rubin, president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences with the news that he and his former colleague from Countryman Associates, Chris Countryman, would be receiving an Academy Award for Technical Achievement for their work on a series of sub-miniature lavalier microphones.

Inan, whose research focuses on wearable health monitoring technologies, began working at Countryman while he was finishing his doctoral studies at Stanford University. As a course TA, he was asked to share a job description for internships at Countryman Associates, a Menlo Park, California-based manufacturer of direct boxes and microphones used by audio professionals around the world. The opportunity appealed to him, so he applied, and along with several of his students, began interning. He worked part-time at Countryman as a design engineer for the final two years of his doctoral studies, from 2007 to 2009.

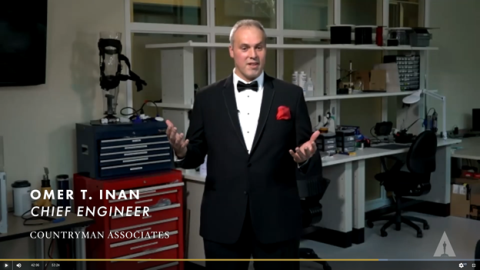

Upon graduating, Inan started full-time with Countryman as chief engineer from 2009 to 2013. While there, Inan and Chris Countryman improved on the B3 and B6 lavalier microphones invented by the company’s founder and Chris’s father, Carl Countryman.

“Those years included a combination of better understanding our own designs, and then learning how to improve upon them; I really enjoyed the challenge of it,” said Inan.

The term lavalier refers to a pendant that hangs from a necklace and is thought to get its name from the French actress Eve Lavalliere (1866 – 1929). In the mid-20th century as film and television began to flourish, actors and presenters would wear cigar-size personal microphones hung from their neck with a cord.

Lavalier microphones became smaller and smaller as engineering improved. Modern day lavaliers can now be hidden in plain sight almost anywhere—in a person’s hairline, behind a shirt button, in a pair of eyeglasses, or in a flower arrangement—and are used in a variety of entertainment settings including live theater, concerts, television, and motion pictures.

In addition to the B3 and B6, Inan and Countryman also designed the B2D lavalier microphone. Differing from the B3 and B6 which are omnidirectional and capture sound from all directions, the B2D is a directional microphone which is particularly suited to a loud environment as it isolates sound coming from a specific source, like an actor’s voice, and dulls ambient noise.

The Technical Achievement Award is for the series of B3, B6, and B2D Countryman lavalier microphones. These lavalier microphones lead the industry due to their small size, rugged construction, and high-quality output. Each product in the series is designed to be easily hidden, extremely durable, and able to provide full frequency sound pickup without compromising the visual aesthetics of a scene. The B6 and B2D microphones are also the smallest in the world, measuring the diameter of a No. 2 pencil lead.

Inan thrived at Countryman and valued the benefits of working with a tight-knit engineering team at a small family-owned business. In addition to the design team, the Menlo Park headquarters of Countryman also included the production line, with injection molding, soldering, audio testing, mechanical fixtures, painting stations, and all of the elements required for producing these high-quality products. For Inan, the satisfaction of seeing products that he and Countryman conceived with the other engineering team members go from concept to prototype to final product, all under the same roof, was both exciting and rewarding. He particularly enjoyed working with Countryman, who was a fellow Stanford alumnus.

“Chris and I had complementary skill sets. It was a great partnership bouncing ideas off one another. We worked hard but had fun in a truly unique environment. We set high standards for the products we wanted to develop, always aiming for industry-leading technical performance, but also loved to listen for hours to some of our expert users around the world telling us about their needs,” said Inan.

Inan also loved traveling around the country and meeting users in person. Hearing about the problems they encountered, seeing their environment, and getting their feedback on sound and usability was invaluable in turning out award-winning equipment. He found himself on theatrical stages, in television studios and theme parks, and fitted everyone from newscasters to CEOs with microphones unique to their needs.

Working with sound engineers onsite, he learned how to hide the microphones and cabling on a user’s body with tape and other fasteners all while meticulously testing the frequency response and quality of the audio output.

What Inan didn’t know at the time was how these experiences in industry would impact his future research endeavors. After starting as an assistant professor at Georgia Tech in 2013, the connection between his work at Countryman and his interest in medical devices and non-invasive physiological monitoring of disease began to merge.

Inspired by his past as a varsity track and field athlete at Stanford, Inan had the interesting idea that a knee brace could include miniature microphones to capture the subtle sounds produced by the knee during movement.

“I became curious about how these sounds might reflect the underlying health of the structures and tissues within the knee, such as ligaments, the meniscus, and the cartilage. While the research problem required advanced engineering and computing capabilities completely outside the domain of audio—machine learning, embedded systems design, and biomechanics to name a few—the idea of taping miniature microphones and accelerometers to the body to accurately sense acoustics with high fidelity was a familiar concept,” said Inan.

This idea from Inan started as a bench-top prototype that his graduate students wheeled together with him to the Bobby Dodd Stadium at Georgia Tech for initial testing with student-athletes convalescing injuries. Through these initial studies, Inan’s group learned about the nuances of joint sounds, how to accurately measure them, and how to process them to extract meaningful information. Since then, the group has improved the hardware and the data analytics aspects of the work, with the most recent implementation of the device being an instrumented knee brace deployed in clinical studies at two different sites.

One question Inan got over and over was about the famous golden “Oscar” statuette. How heavy is it? Where would he put it? Some were sad to learn that Technical Achievement Awards get a certificate, not a statuette. When ECE faculty, staff, and students found out that he wouldn’t receive the well-known trophy, a team set to work and made a 3D printed version of Oscar in the Interdisciplinary Design Commons (IDC) makerspace. The one-of-a-kind statuette was presented to Inan. The gesture was a touching surprise and a perfect culmination to his brush with Hollywood.

When Inan was interviewed by the Academy for their online ceremony which aired February 13, 2021, he attempted to end with a joke about mic-dropping.

“I tried to make what ended up being a total Dad-joke about dropping the mic, but if it was a Countryman lavalier it wouldn’t be very impressive because it’s so small. It fell a bit flat,” he laughed.

But he ended up with his own personal mic-drop moment, anyway.

“This statuette is a really fitting end to this Academy Award adventure and how the technology ended up in my research at Georgia Tech. It symbolizes the ingenuity, creativity, and community here and honestly this plastic 3D printed version means more to me than the real thing,” said Inan.

Additional Images